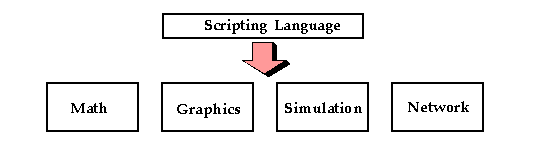

A real application might look more like this :

In either case, we are interested in controlling a C/C++ program with a scripting language interface. Our interface may be for a small group of functions or a large collection of C libraries for performing a variety of tasks. In this model, C functions are turned into commands. To control the program, the user now types these commands or writes scripts to perform a particular operation. If you have used commercial packages such as MATLAB or IDL, it is a very similar model--you execute commands and write scripts, yet most of the underlying functionality is still written in C or Fortran for performance.

The two-language model of computing is extremely powerful because it exploits the strengths of each language. C/C++ can be used for maximal performance and complicated systems programming tasks. Scripting languages can be used for rapid prototyping, interactive debugging, scripting, and access to high-level data structures such as lists, arrays, and hash tables.

for (i = 0; i < 1000; i++) {

call a bunch of C functions to do something

}

or writing the same thing in Python :

Most of the time is still spent in the underlying C functions. Of course, you wouldn't want to write the inner loop of a matrix multiply in a scripting language, but you already knew this. It is also worth noting that reimplementing certain operations in C might not lead to better performance. For example, Perl is highly optimized for text-processing operations. Most of these operations are already implemented in C (underneath the hood) so in certain cases, using a scripting language may actually be faster than an equivalent implementation in C.for i in range(0,1000): call a bunch of C functions to do something

My personal experience has been that adding a scripting language to a C program makes the C program more managable! You are encouraged to think about how your C program is structured and how you want things to work. In every program in which I have added a scripting interface, the C code has actually decreased in size, improved in reliability, become easier to maintain, while becoming more functional and flexible than before.

int fact(int n) {

if (n <= 1) return 1;

else return n*fact(n-1);

}

In order to access this function from a scripting language, it is necessary to write a special "wrapper" function that serves as the glue between the scripting language and the underlying C function. A wrapper function must do three things :

As an example, the Tcl wrapper function for the fact() function above example might look like the following :

int wrap_fact(ClientData clientData, Tcl_Interp *interp,

int argc, char *argv[]) {

int _result;

int _arg0;

if (argc != 2) {

interp->result = "wrong # args";

return TCL_ERROR;

}

_arg0 = atoi(argv[1]);

_result = fact(_arg0);

sprintf(interp->result,"%d", _result);

return TCL_OK;

}

int Wrap_Init(Tcl_Interp *interp) {

Tcl_CreateCommand(interp, "fact", wrap_fact, (ClientData) NULL,

(Tcl_CmdDeleteProc *) NULL);

return TCL_OK;

}

When executed, Tcl will now have a new command called "fact" that you can use like any other Tcl command.

While the process of adding a new function to Tcl has been illustrated, the procedure is almost identical for Perl and Python. Both require special wrappers to be written and both need additional initialization code. Only the specific details are different.

double My_variable = 3.5;

It would be nice to be able to access it from a script as follows (shown for Perl):

$a = $My_variable * 2.3;

Unfortunately, the process of linking variables is somewhat problematic and not supported equally in all scripting languages. There are two primary methods for approaching this problem:

SWIG supports both styles of variable linking although the latter is more common. In some cases, a hybrid approach is taken (for example, the Tcl module will create a pair of set/get functions if it encounters a datatype that Tcl can't support). Fortunately, global variables are relatively rare when working with modular code.

Dealing with objects is a tough problem that many people are looking at. Packages such as CORBA and ILU are primarily concerned with the representation of objects in a portable manner. This allows objects to be used in distributed systems, used with different languages and so on. SWIG is not concerned with the representation problem, but rather the problem of accessing and using C/C++ objects from a scripting language (in fact SWIG has even been used in conjunction with CORBA-based systems).

To provide access, the simplist approach is to transform a structure into a collection of accessor functions. For example :

struct Vector {

Vector();

~Vector();

double x,y,z;

};

When accessed in Tcl, the functions could be used as follows :Vector *new_Vector(); void delete_Vector(Vector *v); double Vector_x_get(Vector *v); double Vector_y_get(Vector *v); double Vector_y_get(Vector *v); void Vector_x_set(Vector *v, double x); void Vector_y_set(Vector *v, double y); void Vector_z_set(Vector *v, double z);

% set v [new_Vector] % Vector_x_set $v 3.5 % Vector_y_get $v % delete_Vector $v % ...

The accessor functions provide a mechanism for accessing a real C/C++ object. Since all access occurs though these function calls, Tcl does not need to know anything about the actual representation of a Vector. This simplifies matters considerably and steps around many of the problems associated with objects--in fact, it lets the C/C++ compiler do most of the work.

class Vector {

public:

Vector();

~Vector();

double x,y,z;

};

A shadow classing mechanism would allow you to access the structure in a natural manner. For example, in Python, you might do the following,

>>> v = Vector() >>> v.x = 3 >>> v.y = 4 >>> v.z = -13 >>> ... >>> del v

while in Perl5, it might look like this :

$v = new Vector;

$v->{x} = 3;

$v->{y} = 4;

$v->{z} = -13;

When shadow classes are used, two objects are at really work--one in the scripting language, and an underlying C/C++ object. Operations affect both objects equally and for all practical purposes, it appears as if you are simply manipulating a C/C++ object. However, the introduction of additional "objects" can also produce excessive overhead if working with huge numbers of objects in this manner. Despite this, shadow classes turn out to be extremely useful. The actual implementation is covered later.Vector v v configure -x 3 -y 4 -z 13

my_tclsh is a new executable containing the Tcl intepreter. my_tclsh will be exactly the same as tclsh except with your new commands added to it. When invoking SWIG, the -ltclsh.i option includes support code needed to rebuild the tclsh application.unix > swig -tcl -ltclsh.i example.i Generating wrappers for Tcl. unix > gcc example.c example_wrap.c -I/usr/local/include \ -L/usr/local/lib -ltcl -lm -o my_tclsh

Virtually all machines support static linking and in some cases, it may be the only way to build an extension. The downside to static linking is that you can end up with a large executable. In a very large system, the size of the executable may be prohibitively large.

To use your shared library, you simply use the corresponding command in the scripting language (load, import, use, etc...). This will import your module and allow you to start using it.# Build a shared library for Solaris gcc -c example.c example_wrap.c -I/usr/local/include ld -G example.o example_wrap.o -o example.so # Build a shared library for Irix gcc -c example.c example_wrap.c -I/usr/local/include ld -shared example.o example_wrap.o -o example.so # Build a shared library for Linux gcc -fpic -c example.c example_wrap.c -I/usr/local/include gcc -shared example.o example_wrap.o -o example.so

When working with C++ codes, the process of building shared libraries is more difficult--primarily due to the fact that C++ modules may need additional code in order to operate correctly. On most machines, you can build a shared C++ module by following the above procedures, but changing the link line to the following :

c++ -shared example.o example_wrap.o -o example.so

The advantages to dynamic loading is that you can use modules as they are needed and they can be loaded on the fly. The disadvantage is that dynamic loading is not supported on all machines (although support is improving). The compilation process also tends to be more complicated than what might be used for a typical C/C++ program.

>>> import graph

Traceback (innermost last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in ?

File "/home/sci/data1/beazley/graph/graph.py", line 2, in ?

import graphc

ImportError: 1101:/home/sci/data1/beazley/bin/python: rld: Fatal Error: cannot

successfully map soname 'libgraph.so' under any of the filenames /usr/lib/libgraph.so:/

lib/libgraph.so:/lib/cmplrs/cc/libgraph.so:/usr/lib/cmplrs/cc/libgraph.so:

>>>

What this error means is that the extension module created by SWIG depends upon a shared library called "libgraph.so" that the system was unable to locate. To fix this problem, there are a few approaches you can take.

With a little patience and after some playing around, you can usually get things to work. Afterwards, building extensions becomes alot easier.