or run SWIG as follows :%include pointer.i // Grab the SWIG pointer library

Doing so adds a collection of pointer manipulation functions that are described below. The functions are mainly designed to work with basic C datatypes, but can often be used with more complicated structures.swig -perl5 -lpointer.i interface.i

ptrfree(ptr)

ptrvalue(ptr,?index?,?type?)

void add(double a, double b, double *result) {

*result = a + b;

}

Now, let's use the pointer library (shown for a few languages) :%module example %include pointer.i extern void add(double a, double b, double *result);

# Tcl

set result [ptrcreate double] ;# Create a double

add 4.5 3 $result ;# Call our C function

puts [ptrvalue $result] ;# Print out the result

ptrfree $result ;# Destroy the double

# Perl5

use example;

package example; # Functions are in example package

$result = ptrcreate("double"); # Create a double

add(4.5,3,$result); # Call C function

print ptrvalue($result),"\n"; # Print the result

ptrfree($result); # Destroy the double

# Python

import example

result = example.ptrcreate("double") # Create a double

example.add(4.5,3,result) # Call C function

print example.ptrvalue(result) # Print the result

example.ptrfree(result) # Destroy the double

void addv(double a[], double b[], double c[], int nitems) {

int i;

for (i = 0; i < nitems; i++) {

c[i] = a[i]+b[i];

}

}

# Python function to turn a list into an "array"

def build_array(l):

nitems = len(l)

a = ptrcreate("double",0,nitems)

i = 0

for item in l:

ptrset(a,item,i)

i = i + 1

return a

# Python function to turn an array into list

def build_list(a,nitems):

l = []

for i in range(0,nitems):

l.append(ptrvalue(a,i))

return l

# Now use our functions

a = listtoarray([0.0,-2.0,3.0,9.0])

b = build_array([-2.0,3.5,10.0,22.0])

c = ptrcreate("double",0,4) # For return result

add(a,b,c,4) # Call our C function

result = build_list(c) # Build a python list from the result

print result

ptrfree(a)

ptrfree(b)

ptrfree(c)

struct Point {

double x,y;

int color;

};

You could write a Tcl function to set the fields of the structure as follows :

proc set_point { ptr x y c } {

set p [ptrcast $ptr "double *"] ;# Make a double *

ptrset $p $x ;# Set x component

set p [ptradd $p 1] ;# Update pointer

ptrset $p $y ;# Set y component

set p [ptrcast [ptradd $p 1] "int *"] ;# Update pointer and cast

ptrset $p $c ;# Set color component

}

This function could be used even if you didn't tell SWIG anything about the "Point" structure above.

void add(double a, double b, double *result) {

*result = a + b;

}

It is clear to us that the result of the function is being returned in the result parameter. Unfortunately, SWIG isn't this smart--after all "result" is just like any other pointer. However, with a typemap, we can make SWIG recognize "double *result" as a special datatype and change the handling to do exactly what we want.

So, despite being a common topic of discussion on the SWIG mailing list, a typemap is really just a special processing rule that is applied to a particular datatype. Each typemap relies on two essential attributes--a datatype and a name (which is optional). When trying to match parameters, SWIG looks at both attributes. Thus, special processing applied to a parameter of "double *result" will not be applied to "double *input". On the other hand, special processing defined for a datatype of "double *" could be applied to both (since it is more general).

// Simple example using typemaps

%module example

%include typemaps.i // Grab the standard typemap library

%apply double *OUTPUT { double *result };

extern void add(double a, double b, double *result);

While it may sound complicated, when you compile the module and use it, you get a function that works as follows :

Our function is much easier to use and it is no longer necessary to create a special double * object and pass it to the function. Typemaps took care of this automatically.# Perl code to call our add function $a = add(3,4); print $a,"\n"; 7

int *INPUT short *INPUT long *INPUT unsigned int *INPUT unsigned short *INPUT unsigned long *INPUT double *INPUT float *INPUT

Suppose you had a C function like this :

double add(double *a, double *b) {

return *a+*b;

}

Now, when you use your function ,it will work like this :%module example %include typemaps.i ... extern double add(double *INPUT, double *INPUT);

% set result [add 3 4] % puts $result 7

These methods can be used as shown in an earlier example. For example, if you have this C function :int *OUTPUT short *OUTPUT long *OUTPUT unsigned int *OUTPUT unsigned short *OUTPUT unsigned long *OUTPUT double *OUTPUT float *OUTPUT

void add(double a, double b, double *c) {

*c = a+b;

}

A SWIG interface file might look like this :

In this case, only a single output value is returned, but this is not a restriction. For example, suppose you had a function like this :%module example %include typemaps.i ... extern void add(double a, double b, double *OUTPUT);

When declared in SWIG as :// Returns a status code and double int get_double(char *str, double *result);

The function would return a list of output values as shown for Python below :as follows :int get_double(char *str, double *OUTPUT);

>>> get_double("3.1415926") # Returns both a status and value

[0, 3.1415926]

>>>

A typical C function would be as follows :int *BOTH short *BOTH long *BOTH unsigned int *BOTH unsigned short *BOTH unsigned long *BOTH double *BOTH float *BOTH

void negate(double *x) {

*x = -(*x);

}

Now within a script, you can simply call the function normally :%module example %include typemaps.i ... extern void negate(double *BOTH);

$a = negate(3); # a = -3 after calling this

// Make double *result an output value

%apply double *OUTPUT { double *result };

// Make Int32 *in an input value

%apply int *INPUT { Int32 *in };

// Make long *x both

%apply long *BOTH {long *x};

%clear double *result; %clear Int32 *in, long *x;

The behavior of this file is exactly as you would expect. If any of the arguments violate the constraint condition, a scripting language exception will be raised. As a result, it is possible to catch bad values, prevent mysterious program crashes and so on.// Interface file with constraints %module example %include constraints.i double exp(double x); double log(double POSITIVE); // Allow only positive values double sqrt(double NONNEGATIVE); // Non-negative values only double inv(double NONZERO); // Non-zero values void free(void *NONNULL); // Non-NULL pointers only

POSITIVE Any number > 0 (not zero) NEGATIVE Any number < 0 (not zero) NONNEGATIVE Any number >= 0 NONPOSITIVE Any number <= 0 NONZERO Nonzero number NONNULL Non-NULL pointer (pointers only).

// Apply a constraint to a Real variable

%apply Number POSITIVE { Real in };

// Apply a constraint to a pointer type

%apply Pointer NONNULL { Vector * };

%clear Real in; %clear Vector *;

Before diving in, first ask yourself do I really need to change SWIG's default behavior? The basic pointer model works pretty well most of the time and I encourage you to use it--after all, I wanted SWIG to be easy enough to use so that you didn't need to worry about low level details. If, after contemplating this for awhile, you've decided that you really want to change something, a word of caution is in order. Writing a typemap from scratch usually requires a detailed knowledge of the internal workings of a particular scripting language. It is also quite easy to break all of the output code generated by SWIG if you don't know what you're doing. On the plus side, once a typemap has been written it can be reused over and over again by putting it in the SWIG library (as has already been demonstrated). This section describes the basics of typemaps. Language specific information (which can be quite technical) is contained in the later chapters.

In this case, the third argument takes a 4 element array. If you do nothing, SWIG will convert the last argument into a pointer. When used in the scripting language, you will need to pass a "GLfloat *" object to the function to make it work.void glLightfv(GLenum light, Glenum pname, GLfloat parms[4]);

%inline %{

/* Create a new GLfloat [4] object */

GLfloat *newfv4(double x, double y, double z, double w) {

GLfloat *f = (GLfloat *) malloc(4*sizeof(GLfloat));

f[0] = x;

f[1] = y;

f[2] = z;

f[3] = w;

return f;

}

/* Destroy a GLfloat [4] object */

void delete_fv4(GLfloat *d) {

free(d);

}

%}

When wrapped, our helper functions will show up the interface and can be used as follows :

% set light [newfv4 0.0 0.0 0.0 1.0] # Creates a GLfloat * % glLightfv GL_LIGHT0 GL_AMBIENT $light # Pass it to the function ... % delete_fv4 $light # Destroy it (When done)

While not the most elegant approach, helper functions provide a simple mechanism for working with more complex datatypes. In most cases, they can be written without diving into SWIG's internals. Before typemap support was added to SWIG, helper functions were the only method for handling these kinds of problems. The pointer.i library file described earlier is an example of just this sort of approach. As a rule of thumb, I recommend that you try to use this approach before jumping into typemaps.

% glLightfv GL_LIGHT0 GL_AMBIENT {0.0 0.0 0.0 1.0}

%module example

%typemap(tcl,in) int {

$target = atoi($source);

printf("Received an integer : %d\n", $target);

}

int add(int a, int b);

In this case, we changed the processing of integers as input arguments to functions. When used in a Tcl script, we would get the following debugging information:

In the typemap specification, the symbols $source and $target are holding places for C variable names that SWIG is going to use when generating wrapper code. In this example, $source would contain a Tcl string containing the input value and $target would be the C integer value that is going to be passed into the "add" function.% set a [add 7 13] Received an integer : 7 Received an integer : 13

%typemap(lang,method) Datatype {

... Conversion code ...

}

A single conversion can be applied to multiple datatypes by giving a comma separated list of datatypes. For example :

%typemap(tcl,in) int, short, long, signed char {

$target = ($type) atol($source);

}

%typemap(perl5,in) char **argv {

... Turn a perl array into a char ** ...

}

Finally, there is a shortened form of the typemap directive :

%typemap(method) Datatype {

...

}

%typemap(lang,method) Datatype; // Deletes this typemap

This specifies that the typemap for "unsigned int" should be the same as the "int" typemap.%typemap(python,out) unsigned int = int; // Copies a typemap

This is most commonly used when working with library files.

%typemap(tcl,in) int * {

... Convert an int * ...

}

%typemap(tcl,in) int [4] {

... Convert an int[4] ...

}

%typemap(tcl,in) int out[4] {

... Convert an out[4] ...

}

%typemap(tcl,in) int *status {

... Convert an int *status ...

}

The following interface file shows how these rules are applied.

Because SWIG uses a name-based approach, it is possible to attach special properties to named parameters. For example, we can make an argument of "int *OUTPUT" always be treated as an output value of a function or make a "char **argv" always accept a list of string values.void foo1(int *); // Apply int * typemap void foo2(int a[4]); // Apply int[4] typemap void foo3(int out[4]); // Apply int out[4] typemap void foo4(int *status); // Apply int *status typemap void foo5(int a[20]); // Apply int * typemap (because int [20] is an int *)

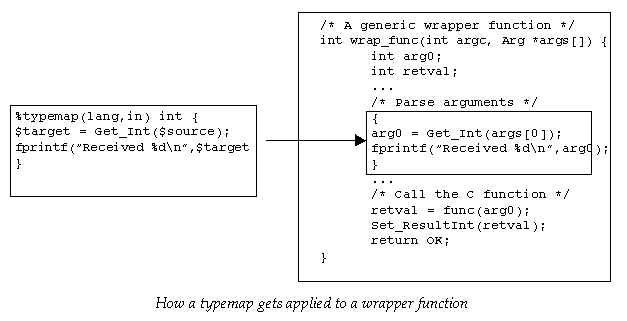

Understanding how some of these methods are applied takes a little practice and better understanding of what SWIG does when it creates a wrapper function. The next few diagrams show the anatomy of a wrapper function and how the typemaps get applied. More detailed examples of typemaps can be found on the chapters for each target language.

%typemap(tcl,in) int *INPUT(int temp) {

temp = atoi($source);

$target = &temp;

}

It is perfectly safe to use multiple typemaps involving local variables in the same function. For example, we could declare a function as :

When this occurs, SWIG will create three different local variables named `temp'. Of course, they don't all end up having the same name---SWIG automatically performs a variable renaming operation if it detects a name-clash like this.void foo(int *INPUT, int *INPUT, int *INPUT);

Some typemaps do not recognize local variables (or they may simply not apply). At this time, only the "in", "argout", "default", and "ignore" typemaps use local variables.

When found in the conversion code, these variables will be replaced with the correct values. Not all values are used in all typemaps. Please refer to the SWIG reference manual for the precise usage.

struct Person {

char name[32];

char address[64];

int id;

};

swig -python example.i Generating wrappers for Python example.i : Line 2. Warning. Array member will be read-only. example.i : Line 3. Warning. Array member will be read-only.

These warning messages indicate that SWIG does not know how you want to set the name and address fields. As a result, you will only be able to query their value.

To fix this, we could supply two typemaps in the file such as the following :

%typemap(memberin) char [32] {

strncpy($target,$source,32);

}

%typemap(memberin) char [64] {

strncpy($target,$source,64);

}

// A better typemap for char arrays

%typemap(memberin) char [ANY] {

strncpy($target,$source,$dim0);

}

Multidimensional arrays can also be handled by typemaps. For example :

// A typemap for handling any int [][] array

%typemap(memberin) int [ANY][ANY] {

int i,j;

for (i = 0; i < $dim0; i++)

for (j = 0; j < $dim1; j++) {

$target[i][j] = *($source+$dim1*i+j);

}

}

The ANY keyword can be combined with any specific dimension. For example :

%typemap(python,in) int [ANY][4] {

...

}

// file : stdmap.i

// A file containing a variety of useful typemaps

%typemap(tcl,in) int INTEGER {

...

}

%typemap(tcl,in) double DOUBLE {

...

}

%typemap(tcl,out) int INT {

...

}

%typemap(tcl,out) double DOUBLE {

...

}

%typemap(tcl,argout) double DOUBLE {

...

}

// and so on...

// interface.i

// My interface file

%include stdmap.i // Load the typemap library

// Now grab the typemaps we want to use

%apply double DOUBLE {double};

// Rest of your declarations

In this case, stdmap.i contains a variety of standard mappings. The %apply directive lets us apply specific versions of these to new datatypes without knowing the underlying implementation details.

To clear a typemap that has been applied, you can use the %clear directive. For example :

%clear double x; // Clears any typemaps being applied to double x

%module math

%typemap(perl5,check) double *posdouble {

if ($target < 0) {

croak("Expecting a positive number");

}

}

...

double sqrt(double posdouble);

This kind of checking can be particularly useful when working with pointers. For example :

%typemap(python,check) Vector * {

if ($target == 0) {

PyErr_SetString(PyExc_TypeError,"NULL Pointer not allowed");

return NULL;

}

}